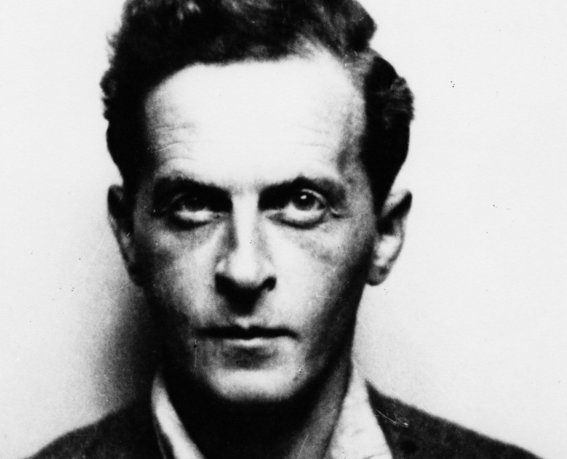

Permission, courtesy of the Joan Ripley Private Collection; Michael Nedo and the Wittgenstein Archive, Cambridge; and the Bodleian Library, Oxford.

„The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.“ – Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889 – 1951)

Intro

Recently, I was listening to a discussion between economics professor Tyler Cowen and LinkedIn creator Reid Hoffman. As the conversation turned to systems and philosophy, two favorite topics of the latter, Dr Cowen posed the inevitable question the tech billionaire gets asked all the time, i.e. how the later Ludwig Wittgenstein had influenced the creation of LinkedIn. If you are interested in the answer, listen here (start at around 17:30).

This prompted me to think back on what I knew about Wittgenstein. I had read his biography many years ago. It had left with me the impression of the tragic though remarkable life of one of the world’s greatest modern philosophers. But what was it again that he had done? With philosophers, unlike natural scientists (but very much like mathematicians), you often have the problem that it is difficult to remember or even understand what they are known for. Alexander Fleming? Penicillin. Edison? The light bulb. Newton? Calculus, the laws of the observable universe, and how not to invest in the stock market.

But Kant, Spinoza, even Plato beyond that dusty cave allegory? It’s worse still with those analytical types from the 20th century. Much like physics, chemistry, and art, once you enter the 20th century, the discourse turns from “yes, sounds great” to “what in the world?!”.

We would have all liked to think electrons behaved like little dots jumping from onion layer to onion layer rather than inhabiting a Heisenbergian hellscape of probability and uncertainty. We can almost all enjoy the aesthetics of works by Michelangelo and Vermeer. However, if you find some of Picasso’s later works “non-pretty” or secretly think “I could have done that, why is he even famous?”, you are far from alone. As is the case with the irate Spanish artist’s oeuvre, beauty often lurks below the surface, abstracted away in a layer of concepts not intelligible to the, as we are told, untrained eye and mind.

Wittgenstein 1.0 – the early years

So what’s the deal with Wittgenstein then? I have always been struck by a curious aspect of his intellectual development. Unlike any other philosopher I know (though this is probably false on closer inspection), there is a common, albeit reductive, practice to differentiate between an “early” and a “late” Wittgenstein. That is, within the same man there are two fellows of apparently entirely different views on the very foundations of their philosophy.

Human language is what Wittgenstein was most interested in. He believed that all philosophical problems are based on a confusion created by unsuccessfully trying to say things that are in fact not sayable. Since we are not clear about what we say, we misunderstand each other constantly. He therefore wanted to understand how language relates to reality to find what might today be called a decryption algorithm for human communication. This practice aimed to define the boundaries of what could and should be said, deeming everything else inutterable. According to him, the unspeakable was at best only capable of being shown rather than being said, e.g. the meaning of virtue is illustrated through living a virtuous life but you cannot describe it because it is not present in reality.

His first iteration, i.e. the early Wittgenstein, believed to have found the solution in formal logic. Things in the physical space are supposedly related to words through logical statements. He called this „picture theory“ because everything in the world can be pictured by language. “A cat is throwing up a furball on the carpet” explained the animal’s position as well as its ontological state, i.e. furballing. Thereby, the structure of reality predetermines the limits of what can be meaningful language. What cannot be pictured, however, such as virtues or ethics, must therefore fall outside the scope of language. They should not be uttered because doing so only leads to nonsense, then confusion and, finally, unsolvable dissent.

Wittgenstein 2.0 – late but great

However, Wittgenstein eventually noticed that many aspects of language use—such as questions, commands, jokes, and expressions of emotion—do not fit neatly into the picture theory. These uses of language do not represent states of affairs in the world, yet they are meaningful and essential to human communication. His experiences as a schoolteacher in rural Austria after World War I played a significant role in his philosophical development. Teaching children and observing their use of language in practical contexts led him to appreciate the diversity and complexity of ordinary language. He saw that meaning is often determined by context, use, and social practices, rather than by a strict correspondence between words and objects.

Thus, the late Wittgenstein was born. With him, the idea of language games („Sprachspiele“) emerged, i.e. the view that language is determined by how people make use of it. Think of how the meaning of the word “bank” changes whether you refer to the side of the river, a bench in German or a credit institute. Another example, and what I have always found more perplexing, are words that can have both a very positive and very negative meaning such as “foda” in Portuguese or „freak“ in both English and German. Even more poignant if absurd is the term “Aladeen” coined in Sacha Baron Cohen’s fictional rogue state of Wadiya, where the confused patient is told that his HIV test came back “Aladeen” leading him to, in turn, sigh in relief and frown in despair.

Linking Wittgenstein to the law

The Austrian thinker thus formulated what lawyers have known all along: language can take on almost any meaning and shape. In fact, statutes, contracts, judicial opinions, and other legal texts function within distinct legal language games. The meaning of legal terms and provisions is shaped by their use in specific contexts, such as courtroom argument, legislative drafting, or negotiation.

Law is inherently „porous“ and „open-textured“ as H. L. A. Hart posed. This means that you will never account for all eventualities when drafting contracts or legislation. Edge cases will arise. But you do not have to be a legal philosopher or even a lawyer to understand this. Everyone who has haggled with their parents as a child knows this to be true: take for example, discussions of what „reasonable bedtime“ means and how special occasions such as birthdays may warrant a derogation from the lex lata. So it is important to mitigate these uncertainties with default rules and interpretive guidelines on how to handle the unforeseen and borderline scenarios. In the end, current common practice rather than immutable logic seems to determine what we mean.

Why might lawyers care?

So why might lawyers want to know about Wittgenstein? Because a lot of times, their professional success is determined by the correct use of language. Sometimes the entire billion-dollar case hinges on just a single phrase or word („reasonable“, „standard“, „foreseeable“ etc.). Lawyers must consider how such legal terms are actually used in practice, rather than relying solely on abstract definitions or their prior understandings. They must stay open-minded. This pragmatic orientation can inform arguments about legislative intent, the purpose of a statute, or the application of precedent.

Wittgenstein’s rule-following paradox highlights the potential for indeterminacy in the application of rules. To put it simply, a rule, no matter how clearly stated, cannot by itself dictate all its future applications. Consider the seemingly straightforward instruction: ‚Follow the arrow.‘ What if the arrow is pointing at a wall? What if there are two arrows? The rule doesn’t inherently contain the answer for every unforeseen circumstance. Its meaning and correct application are learned and sustained through shared human practices, communal agreement, and repeated use. This is precisely what happens in unclear legal cases, where the application of a legal rule is contested. Lawyers and judges must rely on communal standards, analogies, and precedents to resolve such disputes, rather than a purely mechanical deduction from the rule itself.

Conclusion

Familiarity with Wittgenstein’s philosophy equips lawyers with a deeper appreciation of the complexities of legal language and its interpretation. But it also reminds them that the law is a subsection of all human communication and that their professional problems are just a different flavor of what everyone encounters in their daily life. Engaging with the theory behind language can open up a greater sensitivity for the linguistic problems they face.

You don’t need to know physics to be a great soccer player. But understanding friction, force, and spin can improve your awareness of playing with the ball and help you anticipate some unusual situations. Similarly, knowing more about your main tool, language, gives you perspective on what can be said as opposed to what is unsayable, confusing and therefore, ultimately, not convincing.

Further reading

„Wittgenstein: A Very Short Introduction“ by A.C. Grayling

„The Concept of Law“ by H.L.A. Hart

„The Language of Justice“ (University of Cambridge)

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (SEP) – Specific Entries:

Legal Positivism: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/legal-positivism/

Wittgenstein, Ludwig: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/wittgenstein/

Law and Language: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/law-language/

The Nature of Law: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/lawphil-nature/

Schreibe einen Kommentar